Women's Apex scene has lots of passion, but little cash

This is The Final Circle, a newsletter covering sweaty lobbies, filthy casuals and everything in between

Happy International Women’s Day! This feature was slated to run in Fanbyte months ago, then most of the staff was fired and freelance work was killed. It was really difficult to find a home for this piece, unfortunately. I’ve polished it up and split it into two parts; this is the first. If you think this kind of coverage is important, show your support by subscribing.

The women’s pro scene began with a clutch. Elvira “Esdesu” Temirova had lost both of her teammates, leaving her outnumbered in a battle against K1CK Esports. A lot was riding on the outcome of the fight. It was September of 2019, and Esdesu was playing in the biggest in-person tournament Apex esports had ever put on, the $500,000 Preseason Invitational tournament in Krakow, Poland.

Under the bright lights of the studio stage, Esdesu played some of the cleanest Apex of her life. As the remaining players on K1CK struggled to finish her off, she counterattacked with a few well-placed P2020 Hammerpoint shots, killing both opponents and saving her team. Though the unsigned underdogs ultimately finished in fifth place, they walked away with almost $40,000 and a global reputation. Esdesu, who told an interviewer shortly after the tournament that she loves Apex because no one cares if she’s a woman, became an unlikely role model almost overnight.

Isabella “Avuh” Keller, a sixteen year-old female pro, was one of the thousands of fans watching Esdesu frag out at Poland. “I saw her, and I was like, I want to be just like her,” Avuh told me. Avuh had grown up playing the original Titanfall on her brother’s Xbox, but she’d never thought about playing competitively before. Esdesu changed that: “She played Wattson—I learned Wattson.”

For Christmas that year, Avuh’s dad went out and bought her a prebuilt PC. She quickly found teammates and started scrimming with pros. “They really opened my eyes to the competitive side of Apex and how much work people put in.” She met Complexity’s Bowen “Monsoon” Fuller and Ryan “Reptar” Boyd, “the first people in the community to ever acknowledge me. Their words helped me get so far.” Avuh eventually became one of the top 100 players in the ranked ladder. She soon found herself playing with some of the best players in the game, female or otherwise.

In January 2023, more than three years after she saw the Esdesu clutch, Avuh joined TSM. In February, she was on the ranked ladder at #119, a top Predator with about as much RP as Rogue and Skittlecakes.

For a young player full of promise like Avuh, the ALGS is the holy grail of competitive Apex. But the open format of the circuit means that talented girls looking to make a name for themselves are overshadowed by a pro scene that’s almost exclusively male. Informal social structures and a lack of representation at the top makes everything harder for a talented woman trying to make it in the game.

There are notable exceptions, but signed pros and content creators with the largest followings are mostly men. They tend to play with other men. Invitational tournaments with large prize pools solicit the participation of these popular players in a bid for viewership, and if the rules don’t mandate women on teams (many do), the tournaments feature mostly men.

The thrill of watching Esdesu compete on equal footing on the LAN stage in Poland turned out to be a massive outlier rather than the sign of great things to come. Despite TSM nabbing the most dominant players in the women’s scene, female representation at the elite level is elusive, and they get a fraction of the spotlight enjoyed by their male peers.

Janey, one of the best women in the competitive scene, signed to TSM as a content creator in June 2021. But TSM’s own $100,000 prize pool invitational tournament, in October 2022, did not feature her as a team captain. Instead, 20 male professionals were selected, including all three members of the TSM pro roster. Women were then invited onto teams as a requirement of the tournament rules. One former TSM employee with tournament organizing experience criticized the choice on Twitter, pointing out that women could have easily served as captains. Hal didn’t see an issue, replying that “there's a whole category of players that are just woman(sic) for this tourney actually.” “The point is representation, not as a token,” the former TSM employee replied. Later, she deleted her initial tweet.

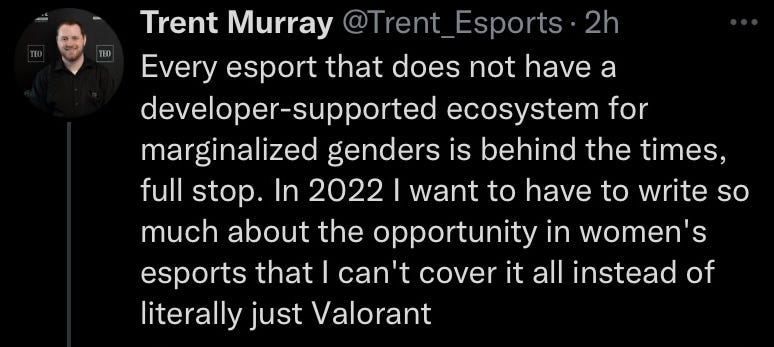

This is hardly a new problem in esports, a space historically unfriendly to women where gender-based harassment is still commonplace. But as more and more women set their sights on careers in competitive gaming, the communities of other games that struggle with misogyny have taken concrete steps to make their pro scenes more inclusive spaces.

Money is a big part of that. Female pros in Counter-Strike and Valorant have more lucrative opportunities than their counterparts in Apex, with dedicated spaces to develop their talent. In February 2021, Valorant introduced Game Changers, a top-tier pro league dedicated exclusively to players of “marginalized genders.” Riot, a company with its own issues relating to the treatment of women, is well aware of the difficulties women face in esports: “Competing in games as a woman can be a daunting task, oftentimes resulting in a very real competitive disadvantage,” explained Anna Donlon, the executive producer of Valorant, in a video announcing the league.

The Counter-Strike scene has followed suit. In December of 2021, ESL announced a $500,000 CS:GO circuit for women. More recent rumors swirling around suggest that Riot plans an all-female circuit for pro League of Legends. Pro Rocket League has dug into their pockets to support women, with teams signing female rosters sponsored by big brands like Mobil 1 and the media conglomerate Sky UK.

There is a thriving grassroots community for aspiring female pros in Apex. But despite record-breaking numbers for ALGS prize pools and its viewership, handsomely-funded opportunities for women have not been forthcoming from EA. In this respect, at least, the Apex esports scene is falling behind its peers. When I asked ALGS commissioner John Nelson about Valorant’s efforts and his own strategy to encourage more female players in competitive Apex in October of 2021, he pointed out the diversity of the game’s characters and said that “it’s been great to see how many women are engaging with the ALGS.” “We are working on specific plans,” Nelson added—which he wasn’t able to divulge then or again in May 2022, when I reached out again for an update.

In the meantime, not every female gamer who cut their teeth on high-level Apex has stuck around. Annie "Aniemal" Lee, who now plays competitive Valorant for Complexity, was originally signed to the organization for her Apex skills. She played in the online ALGS ecosystem during the height of the pandemic, a period in Apex history defined by low morale among pros. Like a handful of other promising players who ended up leaving the game at that time, Aniemal’s competitive Apex career was hamstrung by the canceled Arlington LAN of March 2020. According to Aniemal, “there was a lot of gatekeeping” in pro scrimmages during this chaotic period, and the requirements for participating in them were opaque. She and her teammates found themselves grinding the ranked ladder more and more often instead of joining scrims.

Then a friend of hers, Alice “Ali” Lew, “a CS legend” who had done her own share of work helping to build the women’s scene in that game, reached out to Aniemal about switching to Valorant.

Dedicated and consistent practice has been easier to come by in Valorant, helped along by a larger and better organized community like the 20,000 player-strong Galorants discord. Aniemal never felt that the developers of Apex were helpful or friendly to her as a burgeoning pro. Riot, on the other hand, was “by far, by far, more understanding and like, loving of their game, they actually want their game to flourish and improve. And that's why they put out these like things for women in general as well, because it's like, half of their community is women, right?...And it puts a more fair playing field as well out there, like a more level playing field, for women who have never competed before.”

The women in the Valorant competitive scene have a nearly unprecedented opportunity in esports: to see what they can do when given the opportunity. Splashy promotional material on social media, Twitch drops for in-game cosmetics and a $500,000 Game Changers pool helped make the recent Game Changers championship matches a massive success. With a peak of 239,000 viewers and an average of about 115,000, the Game Changers championship was more than twice as popular as Halo Infinite’s World Championship.

Aniemal praised the grassroots tournaments for women in Apex but also said that the nature of a battle royale lobby, which requires 60 players, is far more logistically difficult to organize than matches in CS:GO or Valorant, which require only ten players.

Even with all the money in the world, the logistics of battle royale seem to reinforce the inequity of the status quo. Fortnite’s FNCS, another battle royale ecosystem with an open professional circuit, has a similar lack of female representation in its competitive scene. Very few of its top players are women, and, like Apex, it has no dedicated women’s only league. But Epic has also taken steps towards increasing gender equity in the game. In a Women’s Day announcement last year, Epic announced they were offering $225,000 in prizes over three women’s-only tournaments on the game’s new zero-build mode.

Despite the lack of first-party tournament offerings, formidable grassroots efforts have helped nurture the women’s Apex scene, serving as an important venue for talent development. But community figures who dedicate significant time and energy to running these events and who believe deeply in the work have struggled to find the viewership and money they need.

In part two of this look at the women’s scene, I’ll address those grassroots efforts and the state of things going forward. Look for that later this week.

Fanbyte wasn’t the only recent casualty in games media. Launcher, the Washington Post’s gaming vertical and the biggest venue for my writing about Apex esports, is shutting down as well. It’s bad out there. I’ve turned on paid subscriptions for this newsletter so that anyone who sees the value in the work can support it financially, but all Final Circle posts are free and always will be.